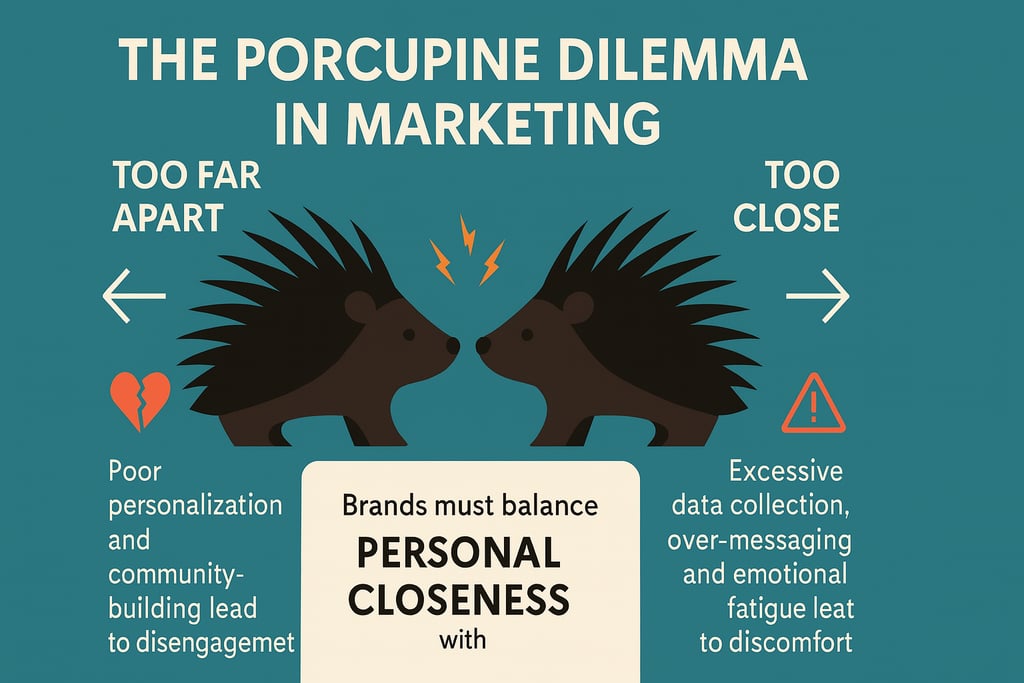

Porcupine Dilemma in Marketing

a metaphor about balancing closeness and distance—perfectly reflects modern marketing. It examines how brands must stay connected to consumers without crossing into intrusion, using real examples, data, and cases to illustrate the fine line between

Mohammad Danish

2/27/20253 min read

Most people don’t associate a spiky 19th-century parable with marketing strategy—but the Porcupine Dilemma explains more about modern brands than many business textbooks do. Originally introduced by philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and later revisited by Sigmund Freud, the dilemma describes porcupines who huddle together for warmth on a winter night. The closer they get, the more they stab each other with their quills. Too far apart, they freeze. Too close, they hurt each other.

Marketers today live in this same tension.

Brands must move closer to consumers—through personalization, community-building, intimate data insights, and constant engagement. But at the same time, getting too close sparks discomfort, distrust, privacy concerns, and emotional fatigue. The paradox is alive everywhere: audiences want connection but dislike intrusion; they want relevance without surveillance; loyalty without overfamiliarity.

And brands, like porcupines, are still figuring out how close is close enough.

Personalization: The Warmth Consumers Want—and the Quills They Fear

A McKinsey study in 2021 showed that 71% of consumers expect personalized interactions, and 76% get frustrated when brands don’t deliver them. Personalization—especially predictive personalization—helps customers feel seen, valued, and understood. But here’s the twist:

Accenture’s Consumer Pulse Study found that over 40% of consumers feel uncomfortable when brands “over-personalize,” especially when the data source isn’t clear.

Case in point?

Case Study: Target’s Pregnancy Prediction Backfiring

Target famously used predictive analytics to identify pregnant customers before they had publicly disclosed it. One teenage girl received maternity coupons mailed to her home. Her father was furious—until he learned the analytics were right. The story became a PR cautionary tale worldwide. Personalization warms the customer. Over-personalization stabs them. That’s the Porcupine Dilemma in action.

Community-Building: Brands Want Intimacy, Consumers Want Boundaries

Community is marketing’s new obsession—Slack groups, Discord servers, insider clubs, NFT communities, VIP programs, and loyalty ecosystems. Harvard Business Review notes that strong brand communities can increase customer lifetime value by 25–100% through emotional attachment.

But too much community-building risks turning into:

Brand fatigue

Over-engagement pressure

One-way “community theater”

Parasocial manipulation

As one consumer summarized in an Edelman Trust report: “I want to belong to a brand community, not be owned by it.”

When brands push too hard—too many messages, too many “touchpoints,” too many nudges—customers retreat. Warmth. Then quills.

Data Collection: Insight vs. Intrusion

Consumers want frictionless experiences, predictive convenience, and personalized journeys. But the moment data collection becomes uncomfortable, intrusive, or opaque, trust collapses.

Example: Meta (Facebook) Cambridge Analytica Scandal. A single incident wiped $119 billion off Meta’s market cap in a day—the largest one-day drop in U.S. history at that time. Why? Because consumers felt the brand came too close, too manipulatively, too invisibly. Privacy concerns are the modern equivalent of porcupine quills: sharp, defensive, and utterly justified.

Brand Tone: Authenticity Without Overstepping

Brands want to feel human. Consumers want brands to feel human too—just not too human. There’s a threshold.

Example: The Wendy’s Twitter Phenomenon. Wendy’s social media team became the gold standard for humorous, edgy brand personality. They built community, drove engagement, and boosted brand visibility.

But when other brands tried replicating it—including Chase, McDonald’s, and even the U.S. Army—audiences felt:

Forced humour

Inauthentic voice

Over-familiarity

Emotional discomfort

Humanness works—until it doesn’t. The Porcupine Dilemma strikes again.

Customer Journeys: Touchpoints vs. Touch Overload

Marketing wisdom has long preached the value of “multiple touchpoints.” But the digital world has multiplied them into:

Emails

Push notifications

Retargeting ads

WhatsApp business messages

SMS offers

Social DMs

App alerts

A Gartner study revealed that 65% of consumers feel overwhelmed by brand communication, and 45% actively avoid brands because of excessive messaging.

Brands want warmth (engagement), but too much warmth melts into irritation. The balance is fragile.

The Middle Path: Managing the Porcupine Distance

Great brands solve the Porcupine Dilemma by mastering empathic distance:

close enough to feel relevant,

far enough to feel respectful.

The most successful brands today—Apple, Patagonia, Airbnb, Spotify—share four strategies:

Value Before Visibility - Brands like Patagonia don't chase customers—they serve them. That creates pull instead of push.

Transparent Data Use - Spotify’s “Wrapped” works because customers know exactly how their data is used—and enjoy the value it returns.

Personalized but Predictable - Netflix personalizes recommendations but explains why: “Because you watched…”; Predictability preserves comfort.

Invite, Don’t Intrude - Apple never “forces” engagement. Its communication is opt-in, never overbearing.

These brands respect the porcupine spacing.

Finding the Sweet Spot

The Porcupine Dilemma shows us that marketing isn’t just strategy—it’s psychology. It’s not just customer acquisition—it’s emotional calibration. It’s not simply communication—it’s relationship management. A brand must be close enough to understand its audience, but not so close that it alarms them. Close enough to create loyalty, but not so close that it suffocates. Close enough to personalize, but not so close that it feels invasive.

The art of modern marketing lies not in the spikes or the warmth—but in the distance between.

Journey well taken

Sharing life insights on marketing and motorcycling adventures.

Connect

Explore

contact@danishspeaks.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.