Muslim Consumers Playing a Pivotal Role in Shaping the Global Economy

Muslim consumers, representing nearly two billion people worldwide, are driving transformative growth across global markets. From halal food and modest fashion to Sharia-compliant finance, their values-based choices are reshaping industries. With rising incomes and ethical demand, they foster financial inclusion, stability, and social equity, positioning Islamic economics as a model for sustainable prosperity.

Mohammad Danish

1/27/20225 min read

Muslim consumers today are playing a pivotal role in reshaping the global economy, not only because of their demographic weight but also because of their growing purchasing power and the values that underpin their consumption. With nearly two billion people worldwide identifying as Muslim, accounting for about a quarter of the world’s population, their impact on international trade, finance, and cultural trends is undeniable. What makes this demographic unique is the intersection of rising wealth, youthful populations, and an increasing demand for products and services that are aligned with Islamic ethics. From halal food and modest fashion to ethical pharmaceuticals, travel, and finance, this consumer segment is expanding beyond its traditional boundaries and influencing business strategies across continents.

This influence is set to grow. With Muslim populations among the youngest globally—median ages in many Muslim-majority countries are under 30—the coming decades will see even greater consumer demand, entrepreneurial innovation, and financial sophistication. The challenge will be ensuring that Islamic finance and halal industries maintain their integrity and do not drift into superficial compliance that undermines their ethical foundations. Standardisation of Sharia interpretations, regulatory frameworks, and education will be critical for sustaining trust and growth. Yet the opportunities are immense: a consumer base that is not only vast and growing but also united by values that prioritise community, fairness, and ethical responsibility.

Muslim consumers are no longer a peripheral market segment; they are central to the global economy’s future trajectory. Their demand is shaping how food is produced, how fashion is designed, how tourism is delivered, and how finance is conducted. Their values are influencing global debates on ethical consumption, inclusive growth, and responsible capitalism. By insisting on alignment between faith, ethics, and commerce, Muslim consumers are showing the world that markets can thrive without abandoning morality. And as Islamic banking demonstrates, finance itself can be reimagined not just as a tool for wealth accumulation, but as a system of shared prosperity. In a time when societies everywhere are searching for models that reconcile growth with fairness, the rise of Muslim consumers provides a powerful reminder that economics, at its best, can be both profitable and profoundly human.

The story of Muslim consumers is not uniform across regions but reflects different trajectories of growth and cultural integration. In Southeast Asia, Malaysia and Indonesia have become leaders in halal certification and Islamic finance, exporting standards and expertise to other markets. In Africa, countries like Nigeria and Sudan are developing their Islamic finance sectors to mobilise capital for infrastructure and social development, recognising that large segments of their populations are more likely to engage with Sharia-compliant services. In Europe, where Muslim minorities are significant in size, mainstream banks such as HSBC and Barclays have opened Islamic finance windows, and governments like the UK’s have issued sukuk to attract Muslim investors and deepen ties with global Islamic capital markets. Even in North America, demand for halal products and Islamic mortgages is steadily increasing, driven by second and third-generation Muslim communities who are asserting both their identity and their purchasing power.

This redistribution element makes Islamic finance particularly interesting in comparison with socialist and social-democratic models. While rooted in religious law rather than political ideology, the outcomes often align with calls for fairness and social equity. By banning exploitative practices like usury and speculation, and by mandating the circulation of wealth through zakat and charitable endowments, Islamic finance ensures that capital serves broader societal purposes rather than concentrating narrowly in the hands of a few. Studies published in journals on development economics have even shown that regions with stronger Islamic banking penetration often experience improvements in human development indices and reductions in income inequality (study). For consumers, this moral and ethical orientation enhances trust in financial systems, reinforcing their preference for Sharia-compliant products and services.

One of the most compelling aspects of Islamic banking is its societal impact. Because it is built on asset-backed transactions and risk-sharing contracts, it tends to be more stable than conventional finance in times of crisis. During the global financial crisis of 2008, for instance, Islamic banks were less exposed to toxic derivatives and speculative lending, enabling them to weather the storm with fewer losses. Research published by the International Monetary Fund has confirmed that Islamic banking development correlates positively with economic growth, even when it constitutes only a small portion of the total financial system (IMF report). Beyond stability, Islamic finance embeds mechanisms of redistribution and social justice. Instruments such as zakat (obligatory almsgiving) and waqf (charitable endowments) are not mere acts of charity but institutionalised systems designed to ensure wealth circulates within society. They fund education, healthcare, housing, and poverty alleviation, directly addressing structural inequalities. Sukuk are increasingly being used to finance infrastructure and sustainable development projects, linking Islamic finance with the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). An OECD study highlights how Islamic finance contributes directly to poverty reduction, economic inclusion, and sustainable growth (OECD report).

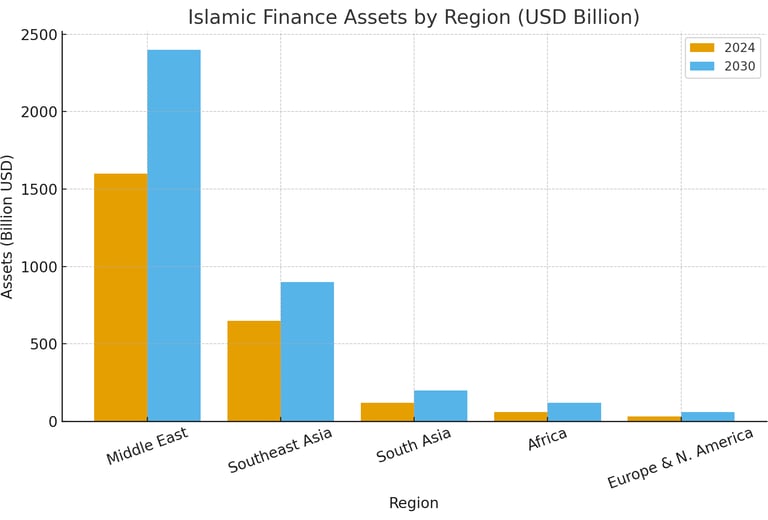

Globally, Islamic finance has grown into a robust industry valued at USD 2.46 billion in 2024 and projected to expand to nearly USD 6 billion by 2033, with a compound annual growth rate of more than 10 percent (source). Its reach extends far beyond the Middle East. In Malaysia, Islamic finance has become a national growth engine, with the country establishing itself as a global hub for sukuk (Islamic bonds) and Sharia-compliant banking. The government’s supportive policies, combined with strong demand from domestic and international investors, have turned Malaysia into a case study for how Islamic finance can drive national development. In the United Arab Emirates, Dubai has positioned itself as the “Capital of the Islamic Economy,” promoting halal tourism, Islamic banking, and global trade platforms that cater specifically to Muslim consumers. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has emerged as the leading Islamic finance centre in the West, issuing sovereign sukuk, creating Sharia-compliant mortgage products, and integrating Islamic finance into its global financial services industry. These examples show how both Muslim-majority and minority nations are leveraging the growth of Islamic finance to enhance competitiveness in the global economy.

The role of Muslim consumers becomes even more significant when examined through the lens of Islamic banking and finance. Unlike conventional financial systems built primarily on interest-based lending and speculative instruments, Islamic banking is guided by Sharia law, which prohibits riba (interest), gharar (excessive uncertainty), and investments in industries deemed harmful, such as gambling, alcohol, and weapons. Instead, it promotes risk-sharing, asset-backed financing, ethical investments, and community welfare. This is not simply a financial preference but a moral framework that appeals to millions of consumers who view finance as part of a holistic ethical life.

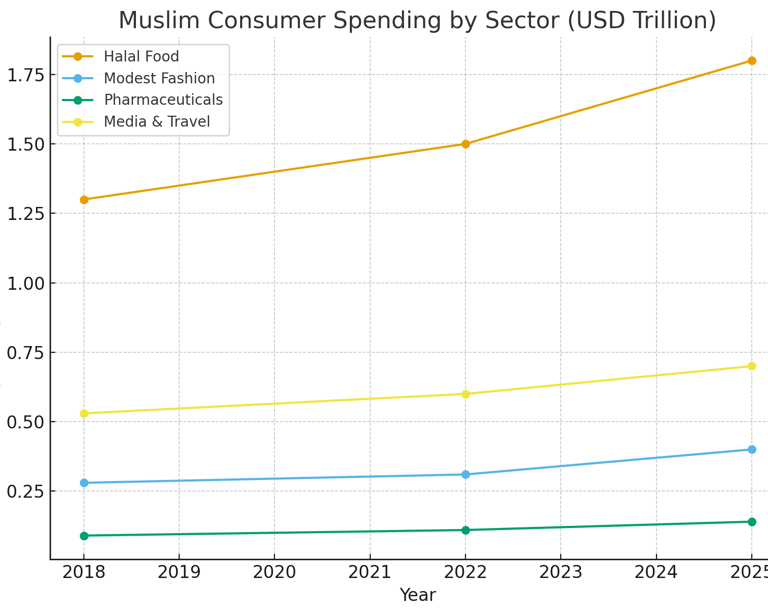

The numbers are striking. According to the State of the Global Islamic Economy Report produced by DinarStandard, Muslim consumer spending across halal food, pharmaceuticals, modest fashion, travel, and media reached USD 2.2 trillion in 2018 and has continued to grow since. Even during economic slowdowns, these sectors have shown resilience, reflecting the strength of faith-based consumer demand. By 2025, projections suggest Muslim consumer spending could surpass USD 3 trillion annually (report link). Multinational corporations from Nestlé to Unilever have responded by diversifying their halal product portfolios, while global fashion houses are launching modest fashion lines to appeal to young Muslim consumers who want modern aesthetics that respect cultural traditions. Airlines, hotels, and even pharmaceutical firms are also adapting their services, signalling that this shift is more than a niche—it is a global mainstream transformation.

Journey well taken

Sharing life insights on marketing and motorcycling adventures.

Connect

Explore

contact@danishspeaks.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.